Introduction

Humankind has always had a great fascination with individuals that are outliers in various aspects of life. Be it the fastest 100 meters sprinter or the tallest person ever. Individuals with such attributes often warrant interest and respect from their surroundings. Still, few concepts warrant more interest than the people who have lived the longest (Milholland & Vijg, 2022). We, as individuals, have a finite time on this earth and most people would give anything to be able to enjoy an extended life. There’s a reason why there was a great interest in discovering the fountain of youth or finding a way to obtain eternal life in the past. This is therefore one of the reasons why there is an interest in finding out who has lived the longest. To complicate this process is the fact that some individuals exaggerate their ages for a variety of reasons to appear older than they actually are. Some do it for pension reasons, others as a result of a mix-up in identities or uncertainty when they were born with, and some do it for notoriety (Schoenhofen et al., 2006).

In my years of researching supercentenarians, I have seen a great deal of age exaggeration with claims of having lived to be older than 115 being common. However, most of these claims are untrue. Still, in the history of supercentenarian research, some supercentenarians have been accepted as validated, only to later have their statuses disputed.

Pierre Joubert (1701? – 1814)

Early research disproved many historical supercentenarian claims from the 18th and 19th centuries, but one person that was believed to have been accurate by demographers was Canadian man Pierre Joubert (Jeune & Poulain, 2020). There existed proof of birth and death for this case, which resulted in the inclusion of Joubert as validated in several lists and by scholars up until the early 1990s, when his age was debunked by revealing that “Pierre Joubert” was actually two individuals; a father and a son and that the father’s date of birth had erroneously been attributed to his son with the same name (Charbonneau, 1990). His validation was swiftly retracted following this revelation.

Thomas Peters (1745? – 1857)

One of many inaccurate inclusions of “verified” exceptional longevity by Guinness World Records. Thomas Peters was allegedly born in the Netherlands on 6 April 1745 and died shortly before his claimed 112th birthday in 1857 (Jeune & Poulain, 2020). Peters claimed to have been a soldier and serving under Napoleon. His parents died when he was a small child, and he grew up as a “regiments-child” in the army. No early-life documentation appears to ever have existed for Peters and his age claim was rather accepted as verified as a result of hearsay. Supercentenarian fans have been trying to identify his age for several years but given the lack of information about his early life it is at present unlikely that any documents will be located. And if they are, they will most likely support him being much younger than claimed.

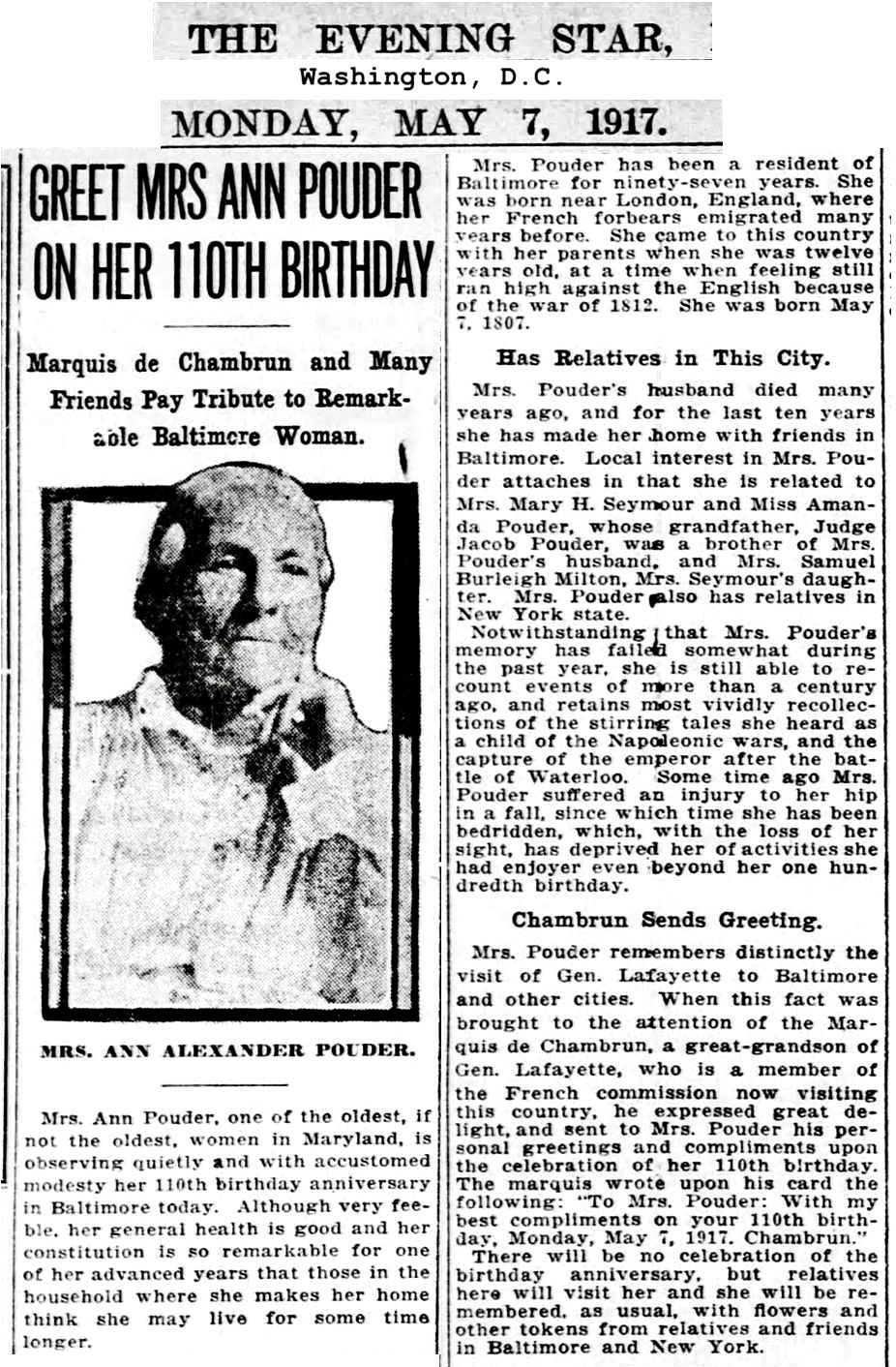

Media coverage of Ann Pouder’s “110th” birthday, inflating her age by one year.

Ann Pouder (1807? – 1917)

Ann Pouder is still considered to be the first American supercentenarian by less serious organizations. She was born in London, England as Ann Alexander and emigrated to the United States at a young age. Her age was supposedly validated by Alexander Graham Bell, but exactly what sort of documentation he utilized is unknown. What however is known is that when Dr. Andrew Holmes and I applied modern validation practices to attempt to verify her age, we discovered that she was in fact not a supercentenarian but rather “only” 109 years old. This was supported by her baptismal record, which was clear with the fact that she was born on 3 May 1808 rather than 8 April 1807. While not as egregious as other claims listed, being one year younger means that she wasn’t a supercentenarian.

Martha Graham (1842? – 1959)

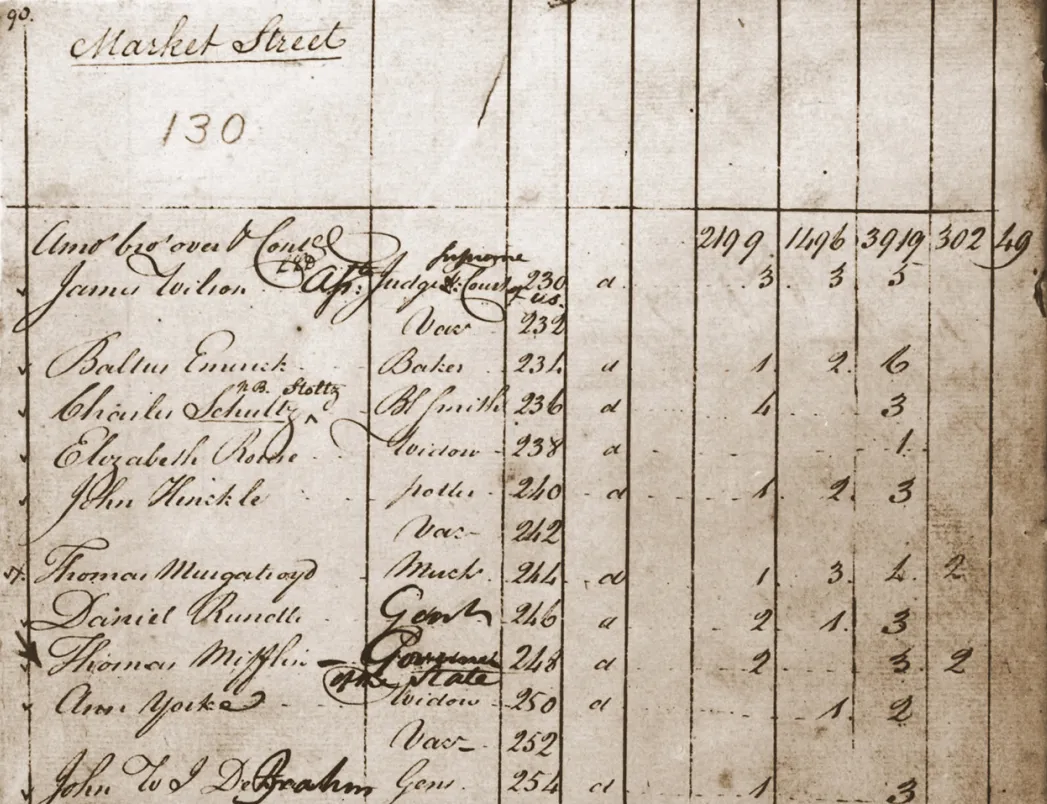

Long recognized as the oldest person ever for about two decades by some organizations was Martha Graham, a former slave from North Carolina, and for whom the best evidence supporting her being a supercentenarian came from the 1880 census, which listed her as 35 years old. While she hasn’t been officially debunked, only disputed, observing her as being only 17 when she married in 1874 suggests that she was about a decade younger, which is further supported by the fact that she had several children under the age of five in the 1900 census. A woman giving birth in her 50s several times in the 1800s is unheard of and her claim can thus be considered exaggerated.

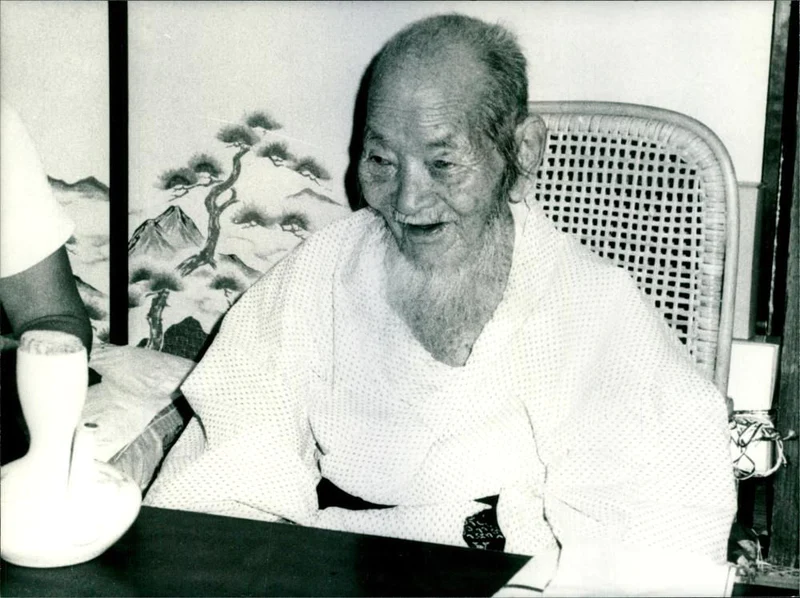

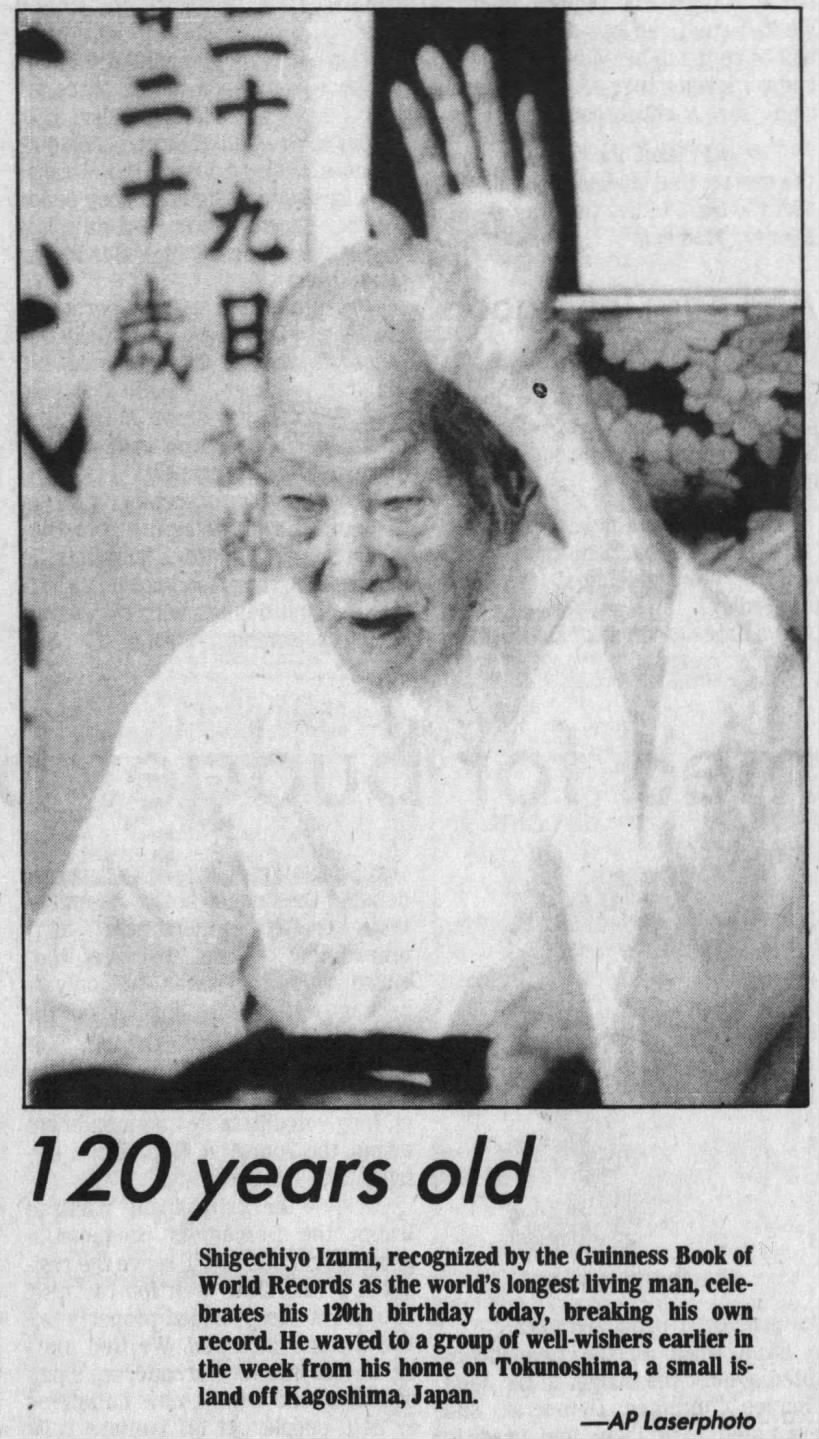

Shigechiyo Izumi, photo courtesy of Associated Press

Shigechiyo Izumi (1865? – 1986)

When Jeanne Calment surpassed the age of 120 years, 237 days, in 1995 she was recognized as the oldest person ever. This is due to the fact that Japanese man Shigechiyo Izumi was still considered validated at this point. Izumi wouldn’t be retracted from most lists until the 2000s. Izumi worked as a farmer and would retire only as an alleged centenarian. While Izumi hasn’t been debunked officially, indications exist that what might have happened is that a younger brother was given the same name as his deceased older brother and thus added a potential 15 years to his listed age (Asahi Shimbun, 1987; Young, 2020). This led to him losing his status as the oldest verified man of all time. There are more issues with his claim, including that his wife also exaggerated her age, which makes the claim to 120 years seem far-fetched.

Matthew Beard (1870? – 1985)

Matthew Beard was at one point considered the oldest man ever. He claimed to have been born in Virginia and lived an eventful life, starting work at a young age and being a war veteran. Beard would settle in Florida and have several children. He supposedly built a house when he was a centenarian. Research by me some years back cast doubt on his claim. A “Mathew Baird” from Tennessee, with parents loosely matching those in Beard’s SS-5 application form, was listed as age 12 in 1880 and age four in 1870, it was possible that this was the person that was linked by researchers to the man that died in 1985. My research did cast doubt on this, especially since this child’s mother had an entirely different last name than what was listed in the SS-5 form. Instead, a match was found for a Matthew Beard born in Georgia in October 1886 with parents that had matching names to his application form. As is, there isn’t any documentation from before 1930 supporting him being a supercentenarian, which makes him disputed.

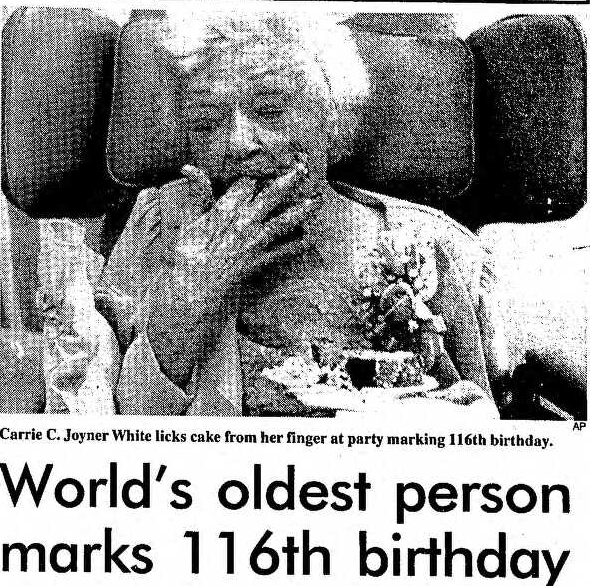

Media coverage of Carrie White’s “116th” birthday

Carrie White (1874? – 1991)

After the death of Florence Knapp in 1988, Jeanne Calment was briefly purported to be the oldest living person in the world. A Florida woman named Carrie White was however later declared as the oldest living person (Young, 2010). It was alleged that White was born in 1874 and that she had resided in a nursing home since the age of 35 when she was committed by her husband as a result of “mental illness.” While mid-life census records did support her being as old as claimed, an examination of her 1900 census revealed that she was actually born in 1888 and only 11 years old. A realization was thus made that the wrong Carrie Joyner had been linked to the Carrie White that died in 1991.

Lucy Hannah (1875? – 1993)

When Hannah died in 1993, she was believed to have been the oldest woman to ever having died, being outlived by Calment by four years. Hannah was allegedly born in Alabama in 1875, although she claimed to have been born in 1874, and to have died in Michigan in 1993. She was likely validated based on a match where a four-year-old Lucy Terrell was living with her grandparents in Alabama in 1880. Research by me revealed that the names of the grandparents of the Lucy Hannah didn’t match these names. Further, a match for her parents in 1880 was found and there was no daughter named Lucy listed. Instead, a marriage record from 1943 was located, where a Lucille Brown (with parents with the exact same names as in Lucy Hannah’s SS-5 form) was listed as having been born in 1895. Given that there now didn’t exist any documentation supporting Lucy Hannah being a supercentenarian, her age was disputed.

Discussion

Supercentenarian research has advanced over the past few decades and the standards for age validation are increasingly more stringent than previously (at least within LongeviQuest). Many people have claimed to have been supercentenarians, but far from all have actually lived as long as claimed. The people listed above are only a few of all exaggerated supercentenarian claims known to exist. There is need for strict validation standards and for research to be re-checked by a fresh pair of eyes every now and then to ensure that the quality of the validation holds up as the amount of available documentation increases.

References

Asahi News Service. (1987). Japanese Expert Debunks Idea of “Village of 100-Year-Olds.” (April 6, 1987).

Charbonneau, H. (1990). Pierre Joubert a-t-il vécu 113 ans? Memoires de la Société génealogique canadienne-francaise, 41, 45–48.

Jeune, B., & Poulain, M. (2020). The First Supercentenarians in History, and Recent 115 + −Year-Old Supercentenarians. An Introduction to the Following Chapters. In: Maier, H., Jeune, B., Vaupel, J.W. (eds) Exceptional Lifespans. Demographic Research Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49970-9_14

Milholland, B., & Vijg, J. (2022). Why Gilgamesh failed: the mechanistic basis of the limits to human lifespan. Nature Aging, 2, 878-884. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00291-z

Schoenhofen, E. A., Wyszynski, D. F., Andersen, S., Pennington, J., Young, R., Terry, D. F., & Perls, T. T. (2006). Characteristics of 32 supercentenarians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(8), 1237–1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00826.x

Young, R.D. (2010). Age 115 or more in the United States: Fact or fiction? In: Maier, H., Gampe, J., Jeune, B., Robine, JM., Vaupel, J. (eds) Supercentenarians. Demographic Research Monographs

Young R. (2020). If Jeanne Calment Were 122, That Is All the More Reason for Biosampling. Rejuvenation research, 23(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2020.2303