To validate the age of a supercentenarian, a high level of proof is required to substantiate their claimed longevity (Poulain, 2010). Documentation standards vary across different countries, with some nations having a longstanding tradition of meticulously recording births and deaths, while others have a relatively shorter history of such practices.

Among the regions boasting the world’s most robust documentation systems is the Nordic area, where church records have served as a staple for several centuries, enabling thorough validations of exceptional longevity. Notably, Sweden stands out as the leading Nordic country in this regard.

Commencing in 1686, Swedish parish priests were mandated to record each birth, marriage, and death within their parish (Wannerdt, 1982). Various additional documentation systems were implemented to aid the priests in maintaining accurate population records. Although the system took some time to be fully implemented, it has been largely complete for the past 250 years. Further details on this will be elaborated in an upcoming article by the author of this editorial.

This editorial will present a case study, shedding light on how Swedish supercentenarians can be effectively researched.

Zachrison (112) when she became the oldest Swedish person of all time. Source: Aftonbladet.

Astrid Zachrison

Astrid Zachrison garnered attention in the Swedish national media from 2006, marking her 111th birthday, until her passing just half an hour into her 113th birthday in 2008 (Bastholm, 2008). News articles chronicling her life highlighted her birthplace as Fliseryd and mentioned her son, Per-Ivan, born in 1928 (TT, 2007). Astrid lived with her son until the age of 106, after which she relocated to a nursing home (Hökerberg, 2007).

While the available information may not reveal much, the Swedish record-keeping system proves invaluable. The Swedish tax agency maintains comprehensive data on every resident, including details about parents, birthplaces, and deaths. This information likely played a pivotal role in Astrid’s initial validation. However, for a retrospective case study, an array of additional resources is now at our disposal compared to 15 years ago.

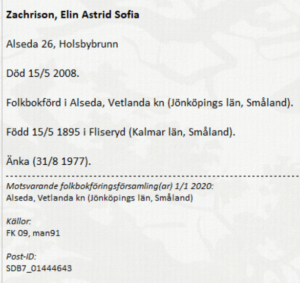

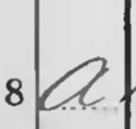

One such resource is the Swedish Death Book 8, encompassing data on individuals who passed away in Sweden between 1830 and 2020.

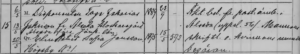

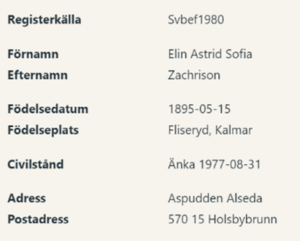

The Swedish death book 8 contains information about every person in Sweden that died between 1830 and 2020. In this book it can be noted that Elin Astrid Sofia Zachrison died in Holsbybrunn on 15 May 2008 and that she had been born in Fliseryd on 15 May 1895. Furthermore, it was noted that she had been widowed in 1977. Her personal identity number (something that is used to identify every person is Sweden) was also listed.

From this death record, there are two search strategies that can be utilized: by going directly to the original documentation from when she was born, or by going backwards from the time of her death to when she was born.

In this instance I chose to start from the time of her birth.

The Swedish National Archives have digitized most Swedish church records and they are publicly available.

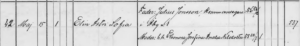

Since Zachrison’s place of birth was Fliseryd, the church books from her birth area were consulted. It can be noted that on page 6 of the christening book for 1895-1912 that Elin Astri Sofia was born to Julius Jonsson (b. 24 December 1856) and Eleonora Josefina Amalia Nilsdotter (b. 28 July 1853) on 15 May 1895. She is noted to have been christened on 18 June the same year. It is further noted that her family was registered on page 537 of the parish roll.

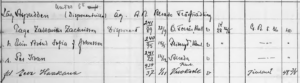

Consulting the parish roll, Elin Astri Sofia can be observed living with her family in the Åby-area of the parish. It is noted that she had several older siblings.

Since the roll ended in 1897, the same can be done on the next roll, which covered the period from 1897-1906. Nothing has changed in the family since there were no children born after Astrid.

Zachrison (right) with her older sister, Ester, c. 1906. Source: https://fliseryd.hemsida24.se/

The parish rolls were originally also used to assess how knowledgeable the parish members were in Christianity, meaning that they received grades from the priests. Astrid Jonsson was still too young to receive such a grade in 1906.

In the parish roll for 1907-1916 it is noted that Astrid received an A in Christianity. Two of her siblings were noted to have left home in 1907, with one later returning.

In the Parish roll for 1917- 1926 it was noted that Astrid Jonsson left home in December 1921 and moved to Högsby, where she worked as an office assistant. She returned home briefly in August 1926.

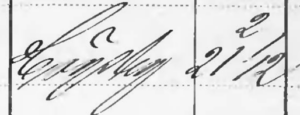

One issue with church books is that the notes can sometimes be close to illegible, which was the case here. It takes some time to get used to reading old Swedish handwriting due to many priests using peculiar writing styles.

One issue with church books is that the notes can sometimes be close to illegible, which was the case here. It takes some time to get used to reading old Swedish handwriting due to many priests using peculiar writing styles.

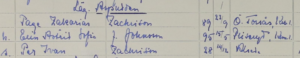

Zachrison was noted to have returned to Högsby in 1926 and would reside at the very same place, which resulted in what appears to be a double entry, but actually contains information about the two separate times she would reside in Högsby.

In the entry for her 1926 return to Högsby there’s a note that she was married in 1928 as the 15th marriage that year. In the marriage books for Högsby, Zachrison’s marriage is recorded: Elin Astrid Sofia Jonsson married Tage Zakarias Zachrison on 26 May 1928.

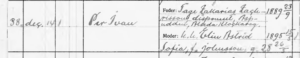

Shortly thereafter it was noted that Astrid Zachrison left Högsby on 26 June 1928 and moved to Klockaregård in Alseda in Jonkoping county. In the entry in the parish book from 1927-1939 for Alseda, Zachrison can be noted to live with her husband and a son, Per Ivan, who was born in December 1928.

Per Ivan Zachrison can be noted in the christening book for Alseda to have been born on 14 December 1928 and that he was the son of Tage Zackrison and Elin Astrid Sofia Johnsson,

In the parish roll for 1940-1949 for Alseda, the Zachrison family lived in the same place, but there was the addition of a Finish-born child named Eeva that had arrived in 1948. This could potentially be related to World War II, which had recently involved Finland.

Newer church books were unavailable since a church document has to be older than 70 years in order for it to be publicly available. This does, however, not hinder further research. Arkiv Digital and Sveriges Släktforskarförbund have several available documents that can aid a researcher in validating the age of a Swedish supercentenarian.

The 1940 Sweden Census is, for instance, available, and in this document the Zachrison family is living in Alseda (which was of course already known from the Parish roll).

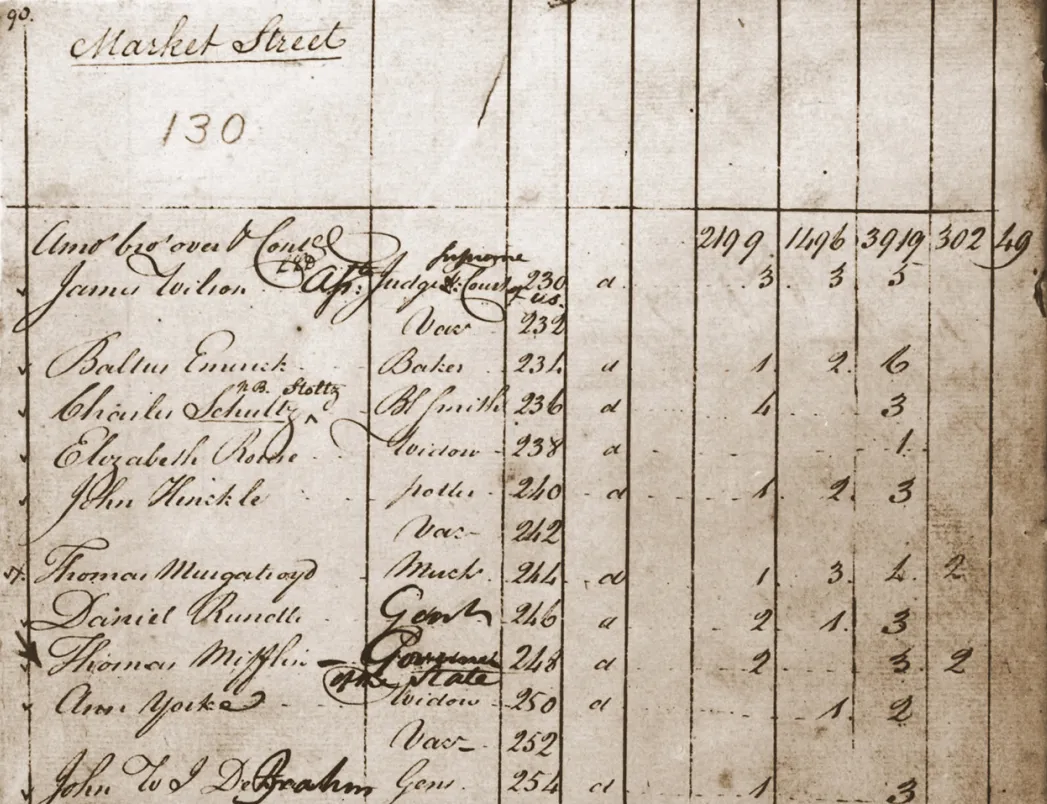

The next document that is available is a mental length. Mental lengths were originally used for taxation purposes but can also be valuable tools in genealogical research. Mental lengths have been compiled for every five or ten years from 1950 to 1990.

In 1950, Astrid Zachrison was noted to be living with her husband and Eeva in Alseda. Meaning that her son had left home by 1950. It was noted that she was also present in the 1946 mental length.

Zachrison can be observed together with her husband in the 1960 mental length, meaning that Eeva had also left by then.

Astrid Zachrison and her husband remained in the same house in 1970 and 1975 as well.

In the 1980 mental length it was however noted that she had been widowed in August of 1977, which was confirmed by her husband’s death index.

In the 1980 mental length it was however noted that she had been widowed in August of 1977, which was confirmed by her husband’s death index.

By 1985, when she was 90 years old, Zachrison still remained in the same house. The same was true for 1990, when she was 95 years old.

Zachrison was reported in the media to have lived with her son until the age of 106, which would likely have been where she would have been found if a document from the time period 1991-2001 had been available. Thankfully, the fact that the personal identity number exists in Sweden means that identity theft can be ruled out for this brief period of time where there isn’t any available documentation. Finally, the death index can be recalled, where it was noted that Astrid Zachrison died in Alseda on her birthday, 15 May 2008, aged 113.

To summarize Astrid Zachrison‘s life:

1895: Born in Fliseryd on 15 May 1895

1895-1921: Lived with family in Fliseryd

1921-1926: Lived in Högsby

1926: Returned briefly to Fliseryd in August before moving to Högsby again

1928: Married Tage Zackrison on 26 May 1928. Moved to Alseda in June. Gave birth to son Per Ivar on 14 December the same year

1928-1977: Lived in Alseda with her husband, being widowed in August 1977

1977-2008: Remained in Alseda until her death at age 113

Summary

There is an ample amount of documentation supporting Astrid Zachrison having lived to 113 years old. The documentation spans her entire life, starting from when she was just one month old. The fact that her date of birth is mentioned in all documents solidifies her age claim. A family tree reconstruction, while not really necessary since she was accounted for throughout her life, also solidifies that Zachrison was a supercentenarian. Given the high quality of the documentation, Astrid Zachrison can be considered a high-level validated supercentenarian.

Family Tree Reconstruction

To spare the details of the same research being performed for all of Astrid Zachrison’s family members, a family tree reconstruction is instead provided here:

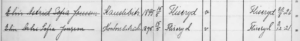

Parents

JONSSON, Julius (24.12.1856 – 27.1.1933)

NILSDOTTER, Eleonora Josefina Amalia (28.7.1853 – 21.11.1944)

Married 20 May 1883

Siblings

JONSSON, Ester Lydia Maria (18.2.1885 – 28.1.1969)

JOHNSON, Josef Julius Amandus (19.10.1886 – 12.6.1968), died in Illinos, USA

JOHNSSON, Karl Artur Alexius (26.1.1888 – 23.10.1956)

JONSSON, Oskar Charodotes Henry (16.4.1890 – 9.7.1962)

JONSSON, Gunnar Arvid Emanuel (24.5.1893 – 4.5.1973)

Spouse

ZACHRISON, Tage Zakarias (23.9.1889 – 31.8.1977)

Married 26 May 1928

Child

ZACHRISON, Per-Ivan (14.12.1929 – 22.11.2022)

References

Bastholm, S. (19 May 2008). Bara tre kvar från 1800-talet. Hallands Nyheter.

Hökerberg, J. (7 Oct 2007). Grattis, Astrid! Aftonbladet.

Poulain, M. (2010). On the age validation of supercentenarians. In Maier, H., Jeune, B., Robine, J-M., & Vaupel, J. W. (Eds.). Supercentenarians. Springer. Demographic Research Monographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-11520-2_1

Tidningens Telegram. (16 May 2007). Sveriges Äldsta fyllde 112 år.

Wannerdt, A. (1982). Den svenska folkbokföringens historia under tre sekler. Swedish Tax Agency. Retrieved 7 December 2023 from: https://www.skatteverket.se/privat/folkbokforing/attvarafolkbokford/folkbokforingenshistoria/densvenskafolkbokforingenshistoriaundertresekler.4.18e1b10334ebe8bc80004141.html