Some attribute longevity to a healthy diet and exercise while others claim that it’s due to habits such as drinking a glass of wine or eating chocolate. While certain such lifestyle choices definitely play a role in helping to extend one’s life, there are many other factors which determines a person’s longevity.

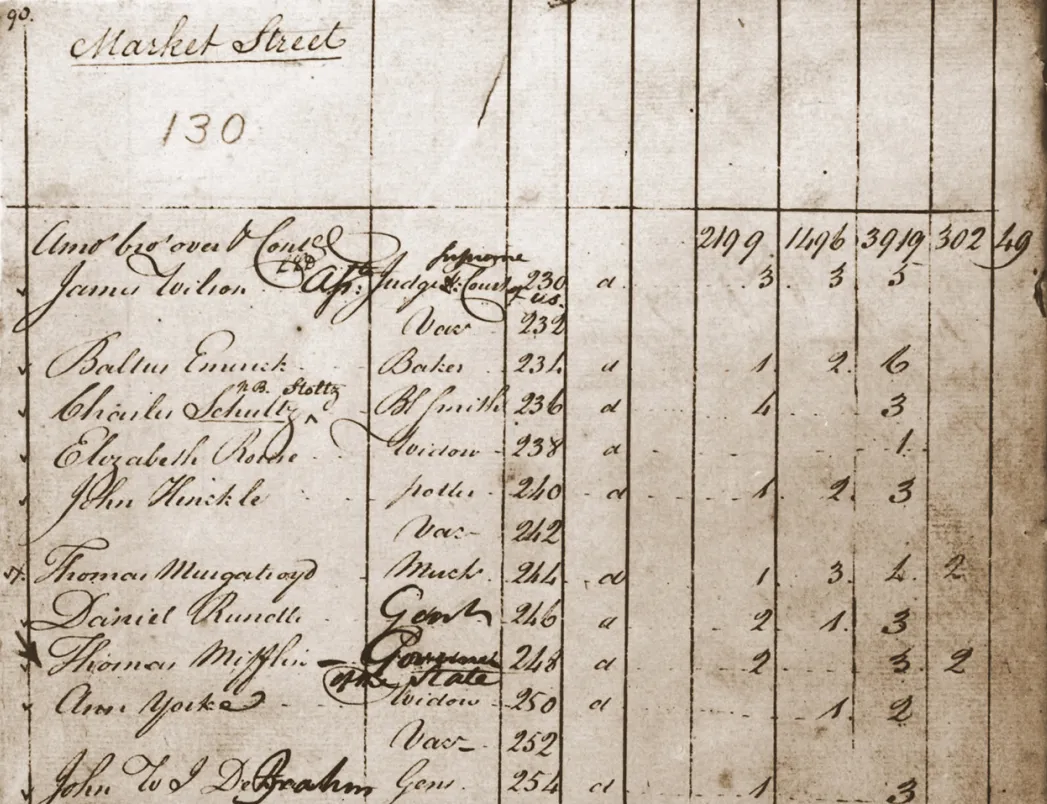

The human genome was only fully mapped in 2003 but, even before that, researchers had turned their attention to analyzing the DNA of people all over the world to understand disease patterns and why a people might develop certain conditions (Smith, 2017; Tamhankar et al., 2021). This also ties in to living a long life. Many centenarians and supercentenarians have siblings, parents or children who have also lived exceptionally long lives (Perls et al., 2002). Research has shown that approximately 20 to 40 percent of human life expectancy might be inherited from generation to generation (van den Berg et al., 2019). There are several explanations as to why longevity clusters in this way, but it can partially be attributed to mechanisms such as a different lipid metabolism (Vaarhorst et al., 2011) or a lack of genes associated with chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders (Bin-Jumah et al., 2022).

Garagnani et al. (2021) performed whole-genome sequencing of people aged over 105 in Italy and compared them with people in their late 60s and found that the long-lived do indeed have a unique genetic background and that their DNA had efficient repair mechanisms. Other human genes, such as APOE (associated with cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer disease) and FOXO3A (insulin/IGF1 signaling) have also been suggested as candidates for affecting human longevity (Huebbe et al. 2011; Hsin & Kenyon, 1999)

Still, little research on the genes behind exceptional longevity has been performed on actual humans due to inherent ethical concerns. Instead, most of the current research on longevity focuses on other organisms, such as yeast, fruit flies and mice (Passarino et al., 2016). So far, these studies have revealed several interesting results and identified several genes associated with longevity (DeGregori, 2020). A gene found in a naked mole rat that was transferred to mice was also found to enhance the longevity of the mice (Zhang et al., 2023). Similarly, gene therapy and gene reprogramming in mice was found to extend their median remaining lifespan by over 100 percent over the control mice (Macip et al., 2024)

While these findings are highly interesting, we must be cautious before applying them to humans. Trying to create transgenic people raises numerous ethical issues (Joseph et al. 2022). First, we must be absolutely certain that the genes that we are trying to transfer to people actually improve their lives. The primary mantra of medicine is “do no harm” which certainly rings true in this situation. Further, exposing people to gene therapies might exacerbate disparities in health, with only certain groups being able to afford the genetic treatments that are being provided. This gap could result in a society where certain socioeconomic strata are able to extend their lifespans by several decades compared to other individuals and thus being able to generate even more wealth that further divide the people in society into in- and outgroups.

What we can do now, at the dawn of a potential genomic revolution, is to concretely identify the association between human DNA and longevity and how we can extend the human lifespan. As mentioned above, there have been some findings that show that centenarians have some distinct markers in their DNA. More research is needed, however, to further map other potential genetic traits that distinguish the long-lived as survivors. Considering how many separate genetic traits humans possess, this is not a simple task. Biosampling is crucial here. A swab of saliva or a simple extraction of a blood sample could potentially reveal the secrets of longevity by identifying genes and certain biomarkers (Chen et al., 2023).

These findings can power significant progress, even beyond creating gene therapies to extend longevity (still a pipe dream today). One day, we may be able to tailor our medical care according to our own unique genomes to eliminate potential risk factors for disease and amplify other traits to extend our own lives here and now. We may be able to create new avenues for promoting healthy aging and simultaneously reduce the burden of age-related disease.

In conclusion, analyzing the DNA of the exceptionally old will be a worthwhile endeavor that will have far-reaching implications for human health and well-being. Researching our DNA holds promise for future generations and can improve the way we approach aging today. As we delve deeper into understanding the key to preventing aging, we move closer to creating a future in which aging is no longer associated with physical and cognitive decline but rather health and vitality.

References

van den Berg, N., Rodríguez-Girondo, M., van Dijk, I. K., Mourits, R. J., Mandemakers, K., Janssens, A. A. P. O., Beekman, M., Smith, K. R., & Slagboom, P. E. (2019). Longevity defined as top 10% survivors and beyond is transmitted as a quantitative genetic trait. Nature communications, 10(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07925-0

Bin-Jumah, M. N., Nadeem, M. S., Gilani, S. J., Al-Abbasi, F. A., Ullah, I., Alzarea, S. I., Ghoneim, M. M., Alshehri, S., Uddin, A., Murtaza, B. N., & Kazmi, I. (2022). Genes and Longevity of Lifespan. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(3), 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031499

Chen, R., Wang, Y., Zhang, S., Bulloch, G., Zhang, J., Liao, H., Shang, X., Clark, M., Peng, Q., Ge, Z., Cheng, C-Y., Gao, Y., He, M., & Zhu, Z. (2023). Biomarkers of ageing: Current state-of-art, challenges, and opportunities. MedComm – Future Medicine, 2(2), e50. https://doi.org/10.1002/mef2.50

DeGregori J. (2020). Of mice, genes and aging. Haematologica, 105(2), 246–248. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.238683

Garagnani, P., Marquis, J., Delledonne, M., Pirazzini, C., Marasco, E., Kwiatkowska, K. M., Iannuzzi, V., Bacalini, M. G., Valsesia, A., Carayol, J., Raymond, F., Ferrarini, A., Xumerle, L., Collino, S., Mari, D., Arosio, B., Casati, M., Ferri, E., Monti, D., Nacmias, B., … Franceschi, C. (2021). Whole-genome sequencing analysis of semi-supercentenarians. eLife, 10, e57849. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57849

Hsin, H., & Kenyon, C. (1999). Signals from the reproductive system regulate the lifespan of C. elegans. Nature, 399(6734), 362–366. https://doi.org/10.1038/20694

Huebbe, P., Nebel, A., Siegert, S., Moehring, J., Boesch-Saadatmandi, C., Most, E., Pallauf, J., Egert, S., Müller, M. J., Schreiber, S., Nöthlings, U., & Rimbach, G. (2011). APOE ε4 is associated with higher vitamin D levels in targeted replacement mice and humans. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 25(9), 3262–3270. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.11-180935

Joseph, A. M., Karas, M., Ramadan, Y., Joubran, E., & Jacobs, R. J. (2022). Ethical Perspectives of Therapeutic Human Genome Editing From Multiple and Diverse Viewpoints: A Scoping Review. Cureus, 14(11), e31927. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.31927

Macip, C. C., Hasan, R., Hoznek, V., Kim, J., Lu, Y. R., Metzger, L. E., 4th, Sethna, S., & Davidsohn, N. (2024). Gene Therapy-Mediated Partial Reprogramming Extends Lifespan and Reverses Age-Related Changes in Aged Mice. Cellular reprogramming, 26(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/cell.2023.0072

Passarino, G., De Rango, F., & Montesanto, A. (2016). Human longevity: Genetics or Lifestyle? It takes two to tango. Immunity & ageing : I & A, 13, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-016-0066-z

Perls, T. T., Wilmoth, J., Levenson, R., Drinkwater, M., Cohen, M., Bogan, H., Joyce, E., Brewster, S., Kunkel, L., & Puca, A. (2002). Life-long sustained mortality advantage of siblings of centenarians. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(12), 8442–8447. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.122587599

Smith M. (2017). DNA Sequence Analysis in Clinical Medicine, Proceeding Cautiously. Frontiers in molecular biosciences, 4, 24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2017.00024

Tamhankar, P. M., Tamhankar, V. P., Vasudevan, L. (2021). Diagnosis of Genetic Disorders by DNA Analysis. In: Dash, H. R., Shrivastava, P., Lorente, J.A. (eds). Handbook of DNA Profiling. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9364-2_30-1

Vaarhorst, A. A., Beekman, M., Suchiman, E. H., van Heemst, D., Houwing-Duistermaat, J. J., Westendorp, R. G., Slagboom, P. E., Heijmans, B. T., & Leiden Longevity Study (LLS) Group (2011). Lipid metabolism in long-lived families: the Leiden Longevity Study. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlands), 33(2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-010-9172-6

Zhang, Z., Tian, X., Lu, J. Y., Boit, K., Ablaeva, J., Zakusilo, F. T., Emmrich, S., Firsanov, D., Rydkina, E., Biashad, S. A., Lu, Q., Tyshkovskiy, A., Gladyshev, V. N., Horvath, S., Seluanov, A., & Gorbunova, V. (2023). Increased hyaluronan by naked mole-rat Has2 improves healthspan in mice. Nature, 621(7977), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06463-0