In some of my past editorials I have discussed early centenarian and supercentenarian claimants. Perhaps the most interesting claimant is Hendrina Link-Scholte(n), who was allegedly born in 1686 and died in 1797 (van Dijk, 2023). With claimants such as her there is always the issue of ensuring that the identity of the claimant matches the person in the birth record. For Mrs. Link-Scholte(n) it has, for example, been understood that she was illiterate and it is therefore a possibility that she didn’t know how old she was and she could potentially have used the identity of an older sibling who died young. But the jury is still out and nothing has, to my knowledge, been found that completely debunks her claim.

While I was out researching supercentenarians at the library a while back, I came across another supercentenarian claimant, this time from Sweden. She was allegedly “validated” in 1989 by a Swedish genealogist, Patrik Perslow and an article was published in the Swedish newspaper Expressen on 8 December 1989.

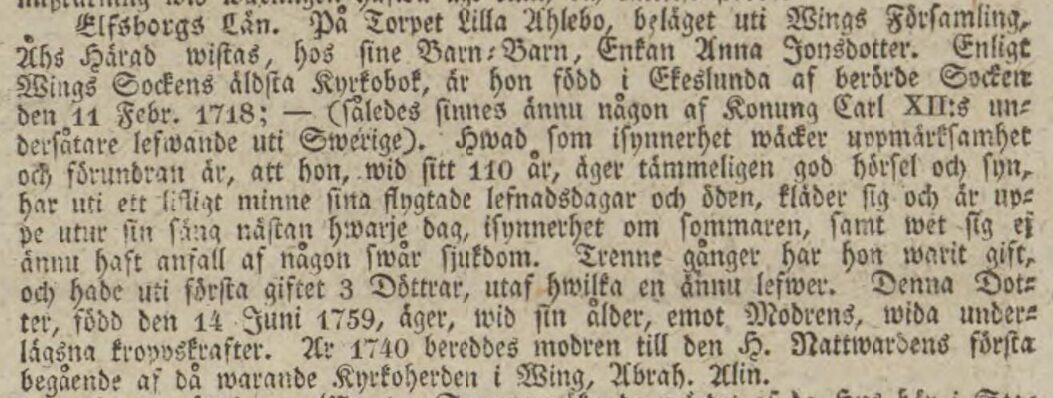

Anna Jonsdotter was allegedly born in Ekeslunda, Wing, Västergötland on 11 February 1718. She attended holy communion in 1740. Jonsdotter was married twice, a mother of three, and had a 70-year-old daughter living at her time of death. Contemporary articles make note that she had good hearing and vision, and was able to get out of bed almost daily, especially in the summer. According to the author in Expressen, Anna Jonsdotter died at the alleged age of 111 years and five months on 1 August 1829. This would have med her the, by far, last living subject of Swedish king Charles XII, who was shot in late 1718.

Swedish church records are generally very reliable, but this is from after the mid-1800s, so the question is if what Jonsdotter claimed was accurate. Can we find evidence supporting the existence of a 111-year-old born back in 1718?

First of all, I checked the death registrations from Södra Ving, which is the southern part of what was known as “Wing,” and there was indeed a mention of a person named Anna Jonsdotter having died in 1829 at age 111.

1829 Death Registration

The death registration states that Anna, daughter of Jons, a widow living in Lilla Alebo, died of old age on 31 July 1829 at the age of 111 years, 5 months and 20 days and was buried on 9 August 1829. So a minor discrepancy of one day regarding her date of death, which is nothing major.

The death registration states that Anna, daughter of Jons, a widow living in Lilla Alebo, died of old age on 31 July 1829 at the age of 111 years, 5 months and 20 days and was buried on 9 August 1829. So a minor discrepancy of one day regarding her date of death, which is nothing major.

Given that we know where she died, the parish rolls (documents that the church used to have an overview of the population) can be consulted.

1824 Parish Roll

The parish roll from 1824 states that Anna Jönsdotter, born in Wing on 11 February 1718 and her daughter Annika Pehrsdotter, born on 14 July 1759 were living in Lilla Ahlebo. A note is made that Anna Jönsdotter died on 1 August 1829.

The parish roll from 1824 states that Anna Jönsdotter, born in Wing on 11 February 1718 and her daughter Annika Pehrsdotter, born on 14 July 1759 were living in Lilla Ahlebo. A note is made that Anna Jönsdotter died on 1 August 1829.

1811 Parish Roll The 1811 parish roll from Lilla Ahlebo makes note that Anna Jonsdotter, born on 11 Feb 1718, was living with her daughter Annika, a likely granddaughter named Sara and a grandson-in-law named Anders.

The 1811 parish roll from Lilla Ahlebo makes note that Anna Jonsdotter, born on 11 Feb 1718, was living with her daughter Annika, a likely granddaughter named Sara and a grandson-in-law named Anders.

A parish roll from 1811 confirming a birth in 1718 sounds promising, right?

1794 Parish Roll

Anna Jonsdotter is listed with her daugher Annika, and four grandchildren, Pehr, Maja, Ivar? and Sara. We now only have a year of birth given for Jonsdotter, 1726.

1777 Parish Roll The 1777 parish roll for Lilla Alebo(da) lists Anna Jonsdotter with her daughter Annica, grandchildren Pehr and Maja and a woman named Ellica with her daughter Sara.

The 1777 parish roll for Lilla Alebo(da) lists Anna Jonsdotter with her daughter Annica, grandchildren Pehr and Maja and a woman named Ellica with her daughter Sara.

Too bad that there’s no age given here. But her age sounds exaggerated, given the 1794 parish roll. But what else can be found?

1759 birth of daughter Annika Persdotter was born on 14 July 1759 to Per Bengtsson and Anna Jönsdotter, which is consistent with what Annika claimed in the parish rolls.

Annika Persdotter was born on 14 July 1759 to Per Bengtsson and Anna Jönsdotter, which is consistent with what Annika claimed in the parish rolls.

1718 Christening? Given that contemporary reports noted that Anna Jonsdotter was born in Ekeslunda, Wing on 11 February 1718 this is a very fitting match with both the correct name, date and place. No parents are listed, which is to be expected from an over 300 year old church book.

Given that contemporary reports noted that Anna Jonsdotter was born in Ekeslunda, Wing on 11 February 1718 this is a very fitting match with both the correct name, date and place. No parents are listed, which is to be expected from an over 300 year old church book.

Can we be sure that this child is indeed the Anna that died at the alleged age of 111 in 1829? No.

When browsing through the list of christenings I can also find a child named Anna Jonsdotter having been born on 3 Nov 1720, but her place of birth does not match what was claimed by the Anna that died in 1829. No other certain matches for an Anna Jons-/Jönsdotter could be located as being born in Wing between 1718 and 1731 and a later birth is unlikely if she took communion in 1740.

So, exactly what do we make of this? We have proof of birth, mid-life-documentation, late-life-documentation and proof of death. Four out of the five documents that give an age are consistent with her claimed age, with the 1794 parish roll supporting her being eight years younger. For some age validators, this would be considered sufficient proof of this person having been a supercentenarian. But since there is also an Anna born in 1720, who could reasonably have been mixed up with the other Anna, it is not enough proof of her age. And if Jonsdotter was actually born in 1720, she would still have been almost 109 years old when she died, which would still be an outstanding age at that time. It is also possible that there is another Anna born later that hasn’t been located.

My working theory is that Anna Jonsdotter did not know when she was born and that when the parish priest came to Lilla Ahlebo and asked for her age, Jonsdotter gave an estimation. The priest later used this information to search the christening registers and found a person who decently matched the age claimed and thereafter entered this birthdate in the parish rolls. This is only a working theory, but given how unlikely an age of 111 in 1829 was, and the age deflation in one of the parish rolls, I believe that it can hold its ground, at least until more is found about Anna Jonsdotter.

I would of course love to be proven wrong and see a supercentenarian born in the early 1700s from my home country. But, I am decently experienced in age validation and understand that you can’t just make up a validation because you want to.

Some other early supercentenarian claimants have had similar issues, a birth registration has been located and linked to the claimant. But these early documents often have too little information to go on, which means that they are not entirely reliable for usage. High standards of age validation need to be employed for all supercentenarians, no matter when and where they were born.

Reference