Technology is the future of care – but are we ready for it?

By Jimmy Lindberg, MSc, and Ben Meyers

Changes in demographics and caregiving

The global population is growing increasingly old due to a plethora of medical innovations and public health strategies that have been implemented during the past century (Zheng et al., 2018). Still, an aging population carries its own problems that need addressing in order for humankind to continue its progress (Christensen et al., 2009). Two such problems caused by the aging population are participation in the workforce and caregiving (Nagarajan & Sizsmith, 2023; Oliver, 2012). A rising average age in the population yields an increasing number of people over the age of 65 and, unless some miracle cure is discovered soon, a good portion of them will require care to maintain a good quality of life with participation in their communities (Ismail et al., 2021; Raggi et al., 2016). While informal care has long been the primary form of caregiving, changes occurred during the 1900s as more people joined the workforce, generating a need for a category of workers to provide care to other people (Nilsson, 2023). Formal care is typically done by professionals that are knowledgeable in caregiving, but it has been observed that professional caregivers are often under an undue amount of stress and have increasingly little time to spend with the people that need care (Zoeckler, 2017; Norström et al., 2023) Additionally, access to professional caregivers is also a question of resources. In some areas it is harder for the people who need care the most to access it (Wray et al., 2021). Further, being cared for by people who are close to you can also provide a sense of reassurance and familiarity (Roth et al., 2015). Thus, informal caregiving has persisted.

An aging population of course includes many individuals living to increasingly old ages. Supercentenarians, people over the age of 110, often outlive some or most of their children. Occasionally, supercentenarian parents and their children reside in the same care facilities. Sometimes the supercentenarian enters the facility first, but other times it is their child. In situations such as these, caregiving becomes complex. In many countries and communities, the child is expected to help provide care for their parent (von Saenger et al., 2023). But when the parent lives to be over the age of 100, the child will also likely be quite old. The oldest known person who had a parent that was still alive was 97 years old at the time of his death (his mother Violet Brown outlived him by a few months). While nonagenarians with living parents are very rare, it raises the question of whether it is feasible for aging children to be the primary caregivers for centenarian parents.

The role of technology and AI in caregiving

Along with the aging population, a technological and digital revolution is simultaneously occurring. Technology is increasingly utilized in all aspects of people’s lives (Alpert, 2023). This naturally includes caregiving and there now exist tools that can be used by both professionals and relatives to help optimize the care that the aging individual receives (Marston & Musselwhite, 2021). While the first tools developed for caregiving were purely mechanical (such as wheelchairs or lifting devices), more recent developments have been made in digital solutions. These solutions include telehealth, which allows for remote monitoring of a person’s health as well as tools for caregivers to both give and receive support (Lindeman et al., 2020). Connecting individuals through digital applications such as social media and video calling apps allows for relationships to be maintained and for better monitoring than only phone calls would have allowed (Kebede et al., 2022; Mueller & Foran, 2019). By being able to provide platforms for both the recipient and caregiver, it is possible to improve the quality of life for both parties.

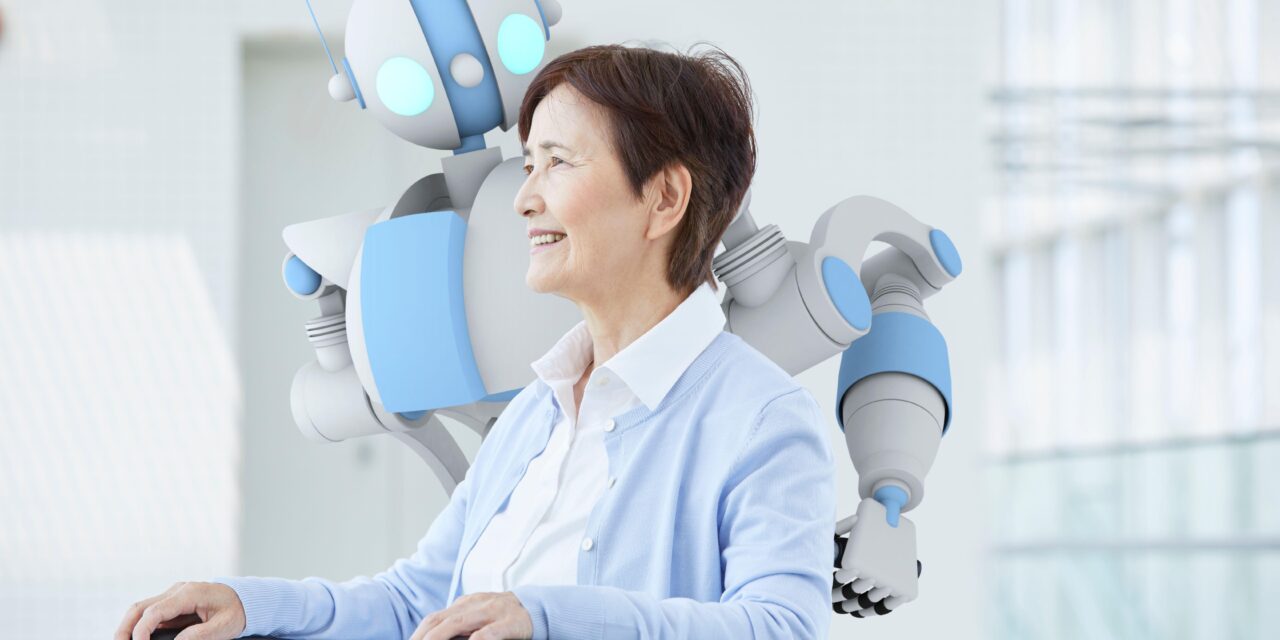

Emerging technology can enable life enrichment and help alleviate loneliness.

The rise of artificial intelligence is also yielding many promising developments that can help augment caregiving efforts (Loveys et al., 2022). One of the key features of AI is its ability to analyze vast amounts of data. This can be useful to train algorithms to develop and create personalized care plans that address the specific needs of each individual (Rony et al., 2024). By providing such plans, a person can receive the care that they need, and it ensures that the older adults can receive the most optimized care that is available. Analytical tools can also help predict future health outcomes by analyzing existing data and thus address these before they escalate to more serious conditions (Han et al., 2023).

The role of the caregiver is complex and multifaceted. The term “caregiver” evokes the physical support element, e.g. feeding, dressing. The medical support element, such as arranging medicines or shepherding a loved one to doctor’s appointments, is distinct but still involves being physically present with the person receiving care. It is difficult today for technology to assist with these aspects of caregiving. AI, machine learning, and robotics are a long way from convincingly simulating the compassion needed for these tasks. The robotics industry seems far from producing an android capable of delicately assisting an elderly person with physical tasks.

Fortunately, AI and machine learning can assist greatly with the administrative side of caregiving (Zawrotny, 2023). This element includes securing proper health care and managing the finances of the person receiving care. It also includes caregivers being forced to address the aftermath of financial fraud involving their loved one. Financial scams against older adults are sadly on the rise, and repairing the damage is a heavy time commitment, dealing with financial institutions and often law enforcement (Waterman, 2023). In the United States, securing proper health care is particularly time consuming. The US health care system, even for older adults, is a byzantine labyrinth of entities whose first instinct is to deflect responsibility. Many older adults, at various points in retirement, will receive health insurance from multiple government entities, namely Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans Affairs administration. For all three, there are entities at the national level and at the US state level, further complicating matters. Similar institutional challenges exist in European health care systems.

This bureaucracy is ill-equipped to address immediate needs. After a fall, older adults may benefit greatly from either time in a physical rehabilitation facility or from an in-home nurse to help prevent a recurrence. These services are needed immediately but can rarely be accessed promptly. This responsibility falls solely on the caregiver. From their perspective, obtaining this care for their loved one is not simply a matter of compassion; it is personally imperative. If the government doesn’t cover the needed services, the caregiver has two choices: 1) take time away from their job to perform the services themselves, or 2) obtain the services without government support at an exorbitant cost. In either case, the caregiver suffers severe financial impacts. This can occur even outside the context of injury or illness; the bureaucracy frequently forces caregivers to justify the care their loved ones already receive (California Medical Association, 2022). The US health care system puts caregivers in these high-pressure situations every day.

Mostly, these administrative activities are done when the caregiver is not physically present with the person receiving care. This creates an important distinction. From the caregiver’s perspective, time on these tasks is simply time spent caregiving. But from the patient’s perspective, the caregiver is absent. This can create a mismatch in expectations. If a caregiver spends several hours on administrative tasks to support their loved one, it reduces the time that caregiver is available to be physically present that day. Many dedicated, diligent caregivers are – in a cruel irony – unable to spend much time in person with the person for whom they are caring. Securing a person’s spot in a US care facility may take hours on the phone with Medicare, with the additional cost of denying the in-person interaction most meaningful for both caregiver and patient. In Maslow’s hierarchy, keeping the older adult in the care home is undoubtedly more important, but physical interaction with a loved one enriches the lives of older adults in incomparable ways. A stark absence of that contact can have an equally strong impact. Time pressure is most intense on caregivers who are also parents, the so-called “sandwich generation” who provide care in both generational directions (University of Michigan College of Medicine, 2022).

The administrative side of caregiving involves many tasks which resemble an office job, especially in terms of correspondence and organization. In this area, AI, machine learning, and robotics are poised to benefit caregiving enormously. It will soon be unnecessary for a caregiver to personally search through gigantic quantities of records to find a needed document. Soon, it will be the caregiver’s AI assistant who spends hours waiting on hold, and when the call is picked up, AI will be able to engage in basic dialogue until the caregiver can join the call (Hold 4 Me, n.d.). Rather than a caregiver spending hours preparing letters and emails to the numerous health care authorities, ChatGPT can do it all in five minutes today. These are just some of the early manifestations of AI. Perhaps soon, AI will enhance security cameras to ensure good treatment of a loved one who may have dementia and is therefore unable to report maltreatment. In this sense, AI could become a permanent patient advocate (Galatas, 2023). Perhaps a machine can prepare a week’s worth of medicines and communicate with generative AI to send refill requests to doctors.

AI can help reduce the workload on caregivers, freeing them up to enjoy more quality time with their loved ones.

Easing the administrative burden on caregivers will have profound effects on both the caregivers themselves and the recipients of care. Caregiving time on a weekly basis often approaches the hours of a full-time job, and the administrative tasks are especially tedious (Luker, 2023). By shifting these activities to AI, caregivers will be freed to focus on the tasks that only they can do and will be able to flourish in their own lives as well. This progress could not be occurring at a better time, with an aging population globally resulting in a smaller pool of caregivers attempting to care for a larger pool of older adults. AI is best equipped to handle the most time-consuming activities, freeing humans to do what only we can do: provide loving care.

Challenges

When looking ahead, the future of AI is promising. Solutions that will be developed in the coming years will help revolutionize the field of caregiving even further than it already has. Technology will reduce the burden of caregiving that relatives and loved ones currently face (Zhai et al., 2023). Tools that monitor and care for the physical health of people in need of care will allow relatives to focus on the more qualitative parts of caring. However, technology can be fickle and while it will undoubtedly bring an array of benefits, there are several hurdles that still need to be overcome and dealt with accordingly before we can fully trust all innovations to enter the homes of potentially vulnerable people. The first major concern relates to the question of privacy and data security (Gochoo et al., 2021). It is a common enough occurrence to read in the news about patient or client data being accessed by hackers. Information such as this is sensitive and data leaks can endanger the recipients. Hackers have existed for a long time and are unlikely to ever go away, hence why safety needs to be guaranteed.

Second is the risk of us relying too much on technology or becoming dependent on it. Technology will likely never fully replace humans, at least not in the more personal aspects of care, which is why we need to strive to establish a proper balance between human care and technology. The authors of this article don’t believe that we would enjoy living out our last years being hooked up to a hyper intelligent AI and not receiving any human contact. Further, technology malfunctions can endanger a person’s safety, such as monitoring systems failing to detect or report emergencies (Schicktanz & Schweda, 2021).

Third is the reluctance to technology held by some individuals (Bertolazzi et al., 2024). While this is likely to decrease as technology grows ever more omnipresent in our daily lives, there is still a need to respect the wishes of each person. Some people might want to receive care solely from other human beings and this needs to be respected (within reasonable limits of course). Helping people understand technology is necessary to ensure that they are comfortable with it (Fleming et al., 2018).

Finally, well not finally since there are so many other aspects that need to be addressed, is the access to care (Chan et al., 2023). We each live in highly developed countries with easy access to advanced health care. Most of the world population does not have this luxury. People who live in poverty or regions where electricity is sparse will not have the same opportunities to receive technology-enhanced care.

Conclusion

Technology is well-equipped to address the needs of our aging population. Technology will lift the caregiving process to new levels. However, there are several issues with technology that need to be addressed as we continue our quest to optimize caregiving.

References

Alpert J. M. (2023). Improving health and the delivery of care using digital technologies: Special issue highlighting innovative approaches to incorporating digital technology into health care. PEC innovation, 3, 100184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2023.100184

Bertolazzi, A., Quaglia, V., & Bongelli, R. (2024). Barriers and facilitators to health technology adoption by older adults with chronic diseases: an integrative systematic review. BMC public health, 24(1), 506. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18036-5

California Medical Association. Federal report finds Medicare Advantage plans often deny necessary care. (2022, May 2). California Medical Association. https://www.cmadocs.org/newsroom/news/view/ArticleId/49741/Federal-report-finds-Medicare-Advantage-plans-often-deny-necessary-care

Chan, D. Y. L., Lee, S. W. H., & Teh, P. L. (2023). Factors influencing technology use among low-income older adults: A systematic review. Heliyon, 9(9), e20111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20111

Christensen, K., Doblhammer, G., Rau, R., & Vaupel, J. W. (2009). Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet (London, England), 374(9696), 1196–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4

Fleming, A., Mason, C., & Paxton, G. (2018). Discourses of technology, ageing and participation. Palgrave Communications, 4, 54. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0107-7

Galatas, A. (2023, September 13). The Future Of AI And Patient Advocacy: A New Era in Healthcare. Greater National Advocates. https://gnanow.org/blogs/the-future-of-ai-and-patient-advocacy-a-new-era-in-healthcare.html

Gochoo, M., Alnajjar, F., Tan, T. H., & Khalid, S. (2021). Towards Privacy-Preserved Aging in Place: A Systematic Review. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 21(9), 3082. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21093082

Han, C. T., Lin, M. C., Alsadoon, A., & Islam, M. M. (2023). Editorial: Artificial intelligence and big data for value-based care. Frontiers in medicine, 10, 1134021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1134021

Hold 4 Me. (n.d.). Www.holdforme.ai. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.holdforme.ai/

Ismail, Z., Ahmad, W. I. W., Hamjah, S. H., & Astina, I. K. (2021). The Impact of Population Ageing: A Review. Iranian journal of public health, 50(12), 2451–2460. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i12.7927

Kebede, A. S., Ozolins, L. L., Holst, H., & Galvin, K. (2022). Digital Engagement of Older Adults: Scoping Review. Journal of medical Internet research, 24(12), e40192. https://doi.org/10.2196/40192

Lindeman, D. A., Kim, K. K., Gladstone, C., & Apesoa-Varano, E. C. (2020). Technology and Caregiving: Emerging Interventions and Directions for Research. The Gerontologist, 60(Suppl 1), S41–S49. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz178

Loveys, K., Prina, M., Axford, C., Domènec, Ò. R., Weng, W., Broadbent, E., Pujari, S., Jang, H., Han, Z. A., & Thiyagarajan, J. A. (2022). Artificial intelligence for older people receiving long-term care: a systematic review of acceptability and effectiveness studies. The lancet. Healthy longevity, 3(4), e286–e297. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00034-4

Luker, G. D. (2023). Taking Time to Recognize Caregivers. Radiology: Imaging Cancer, 5(6), e230191. https://doi.org/10.1148/rycan.230191

Marston, H. R., & Musselwhite, C. B. A. (2021). Improving Older People’s Lives Through Digital Technology and Practices. Gerontology & geriatric medicine, 7, 23337214211036255. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214211036255

Mueller, J., & Foran, H. (2019). Connecting Older Adults and Their Families through Social Technology. European Journal of Public Health, 29(S4). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz186.082

Nagarajan, N. R., & Sixsmith, A. (2023). Policy Initiatives to Address the Challenges of an Older Population in the Workforce. Ageing International, 48, 41–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09442-w

Nilsson, M. (2023). Unpacking The Welfare Technology Solution Discourse [Doctoral dissertation]. Linnaeus University.

Oliver D. (2012). 21st century health services for an ageing population: 10 challenges for general practice. The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 62(601), 396–397. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X653435

Raggi, A., Corso, B., Minicuci, N., Quintas, R., Sattin, D., De Torres, L., Chatterji, S., Frisoni, G. B., Haro, J. M., Koskinen, S., Martinuzzi, A., Miret, M., Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B., & Leonardi, M. (2016). Determinants of Quality of Life in Ageing Populations: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study in Finland, Poland and Spain. PloS one, 11(7), e0159293. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159293

Rony, M. K. K., Parvin, M. R., & Ferdousi, S. (2024). Advancing nursing practice with artificial intelligence: Enhancing preparedness for the future. Nursing open, 11(1), 10.1002/nop2.2070. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.2070

Roth, D. L., Fredman, L., & Haley, W. E. (2015). Informal caregiving and its impact on health: a reappraisal from population-based studies. The Gerontologist, 55(2), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu177

von Saenger, I., Dahlberg, L., Augustsson, E., Fritzell, J., & Lennartsson, C. (2023). Will your child take care of you in your old age? Unequal caregiving received by older parents from adult children in Sweden. European journal of ageing, 20(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-023-00755-0

Schicktanz, S., & Schweda, M. (2021). Aging 4.0? Rethinking the ethical framing of technology-assisted eldercare. History and philosophy of the life sciences, 43(3), 93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-021-00447-x

University of Michigan College of Medicine. “Sandwich generation” study shows challenges of caring for both kids and aging parents. (2022, December 9). University of Michigan College of Medicine. https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/psychiatry/news/archive/202212/%E2%80%9Csandwich-generation%E2%80%9D-study-shows-challenges-caring-both-kids-aging-parents

Waterman, G. (2023, December 8). The National Council on Aging. Www.ncoa.org. https://www.ncoa.org/article/top-5-financial-scams-targeting-older-adults

Wray, C. M., Khare, M., & Keyhani, S. (2021). Access to Care, Cost of Care, and Satisfaction With Care Among Adults With Private and Public Health Insurance in the US. JAMA network open, 4(6), e2110275. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10275

Zawrotny, D. (2023, December 19). The Overlooked Responsibility: The Administrative Side of Family Caregiving. Hmpgloballearningnetwork.com. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/frmc/commentary/overlooked-responsibility-administrative-side-family-caregiving

Zhai, S., Chu, F., Tan, M., Chi, N. C., Ward, T., & Yuwen, W. (2023). Digital health interventions to support family caregivers: An updated systematic review. Digital health, 9, 20552076231171967. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231171967

Zheng, H., & George, L. K. (2018). Does Medical Expansion Improve Population Health?. Journal of health and social behavior, 59(1), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146518754534

Zoeckler, J. M. (2017). Occupational Stress Among Home Healthcare Workers: Integrating Worker and Agency-Level Factors. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 27(4), 524–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048291117742678