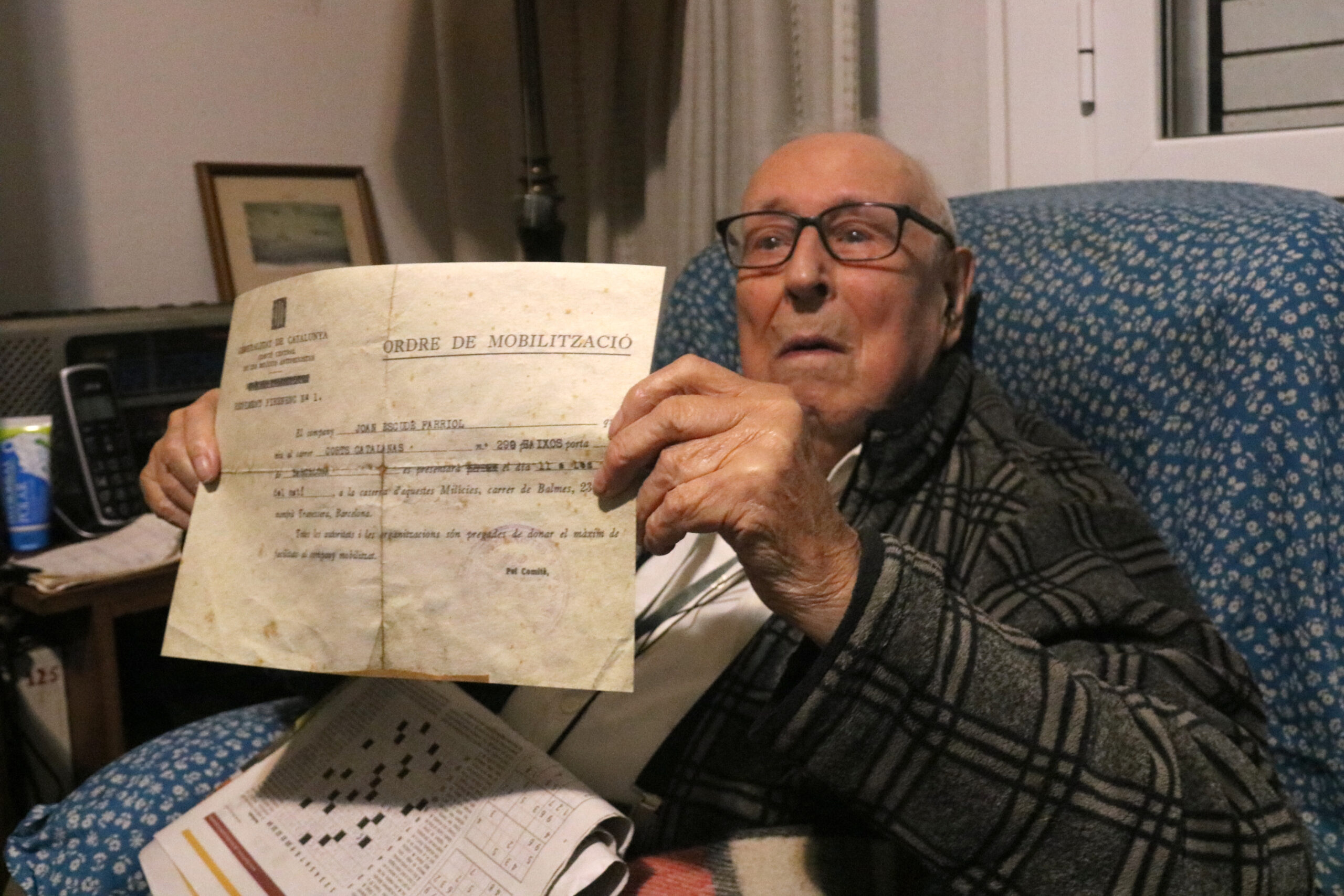

Joan Escudé i Farriol is a Spanish supercentenarian, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, and one of the nation’s oldest living men.

BIOGRAPHY

Joan Escudé i Farriol was born in Capellades, Catalonia, Spain, on 6 January 1916. He grew up in a very humble household where, shortly after his birth, the family fell into extreme poverty. His father died at the age of 33, leaving his mother a widow at just 27. At the time, Joan was only 10 months old, and his mother also had to care for another son who was six years old. His father had owned a small plumbing workshop, but after his death the family was left with nothing. His mother, Pepa Farriol, who could neither read nor write, was forced to raise her two children alone and never remarried.

They returned to the home of Joan’s maternal grandmother, as they could not survive on their own. Poverty prevented him from attending school regularly. After several years living in the family home, his mother was faced with a difficult decision. She and her two children had to leave Capellades in search of better opportunities elsewhere. Their first option was to travel to Argentina, where some cousins had become relatively prosperous. However, she ultimately found work in Barcelona, and the family settled there instead. In March 1927, when Joan was 11 years old, they moved to the city.

Spanish Civil War

Four years later, the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. The company where he worked, which produced religious images of saints, closed as a result of the political changes. His first direct contact with politics came during his teenage years, when he was 15 or 16. Shortly after the religious imagery workshop shut down, he found employment in a workshop run by representatives of the Parker Pen Company. There, he worked as an apprentice salesman and also repaired pens. The owners regularly received a newspaper from Madrid called El Imparcial. Its pages were enormous and consistently hostile toward Catalonia. He later explained that, unable to understand what Catalonia had done to deserve such scorn, he felt compelled to take action. This experience motivated him to join a political party, and he became a member of Estat Català.

On 19 July 1936, he and a friend had planned to meet in Mollet to go hiking. These plans were abruptly interrupted by the military uprising in Barcelona and the outbreak of the Spanish Revolution of 1936. Joan did not leave his house that day, nor did he go out into the streets the following day, having witnessed the fighting. A few weeks after the uprising, Joan became involved in a kind of platoon tasked with requisitioning weapons in the Vallès region. When the Pyrenean Regiment was formed, he enlisted, motivated in part by a desire to see the mountain landscapes. Joan left for Aragon on 1 March 1937. At just 21 years old, he was one of the youngest members of the unit.

For about a month and a half, Joan’s company was stationed in Broto and the surrounding area, fairly close to the front but still far from the front lines. During this period, he and his section carried out road maintenance, control duties, and preventive tasks within the army and the Republican militias, including efforts to prevent soldiers from becoming drunk. They also took part in work on a newly built road, lowering the pavement as part of its construction. He did not receive weapons until June 1937.

When the regiment received its weapons in June, it was assigned to Santa Orosia, a mountain and sanctuary east of Sabiñánigo. A few days later, Joan entered combat at the front for the first time. His unit was subsequently transferred to Belchite. After the attempt to liberate Zaragoza failed, Joan and his companions were sent back to the Aragonese Pyrenees, to the area around Sabiñánigo. There, the regiment—by then integrated into the Popular Army—took part in an offensive at the end of September that briefly allowed Republican forces to retake the towns of Gavín and Biescas. During this attack, Joan was promoted to corporal as a result of his heroic actions, although he did not learn of his promotion until several days later.

Joan spent the final months of the war on the Ebro front. Between late December 1938 and early January 1939, rebel forces broke through the Republican defenses along the Noguera Pallaresa, the Segre, and the Ebro. In little more than a month and a half, Catalonia was occupied by fascist forces, forcing Joan into exile. For four months, from 7 February to 2 June 1939, he endured harsh conditions in French concentration camps in Northern Catalonia.

Returning to Spain

According to Joan, the French authorities sought to recruit the internees into foreign workers’ battalions to fight in World War II, but he refused. He felt it was preferable to return to Spain rather than assist the French, whom he believed had treated the Republic very poorly. For this reason, among others, Joan returned to Spain after his release from the Barcarès camp. On 2 June 1939, he arrived in Figueres and returned to Barcelona the following day.

Finding work in the months that followed was nearly impossible. His former employer refused to rehire him because of his political background and his association with separatist movements.

Later Life

Some time later, Joan finally found work. His brother, a typewriter mechanic, helped him secure a position in a semi-clandestine workshop that repaired typewriters. He also took on a second job in the afternoons, working for a Falangist who had been imprisoned and kept hidden from control patrols throughout the war.

Joan spent thirty months in Aragon completing his compulsory military service, from June 1940 to November 1942—six months less than the usual term.

When he returned to Barcelona after completing his service, there were no longer any typewriters left to repair. He therefore kept the afternoon job he had held before his enlistment and gradually began to rebuild his life. In 1945, he married, and the couple later had three children, one of whom died at the age of five. In 1952, he moved into the apartment where he would live for the rest of his life, eventually purchasing it years later.

RECOGNITION

His age has not been validated.

ATTRIBUTION

* “Memòria viva d’una guerra al Pirineu” – lamira.cat

* “L’home més vell de Catalunya fa 110 anys: “Procuro donar les menors molèsties possibles“” – Diari de Girona, 6 January 2026

Related Profiles

[crp limit=’4′ ]