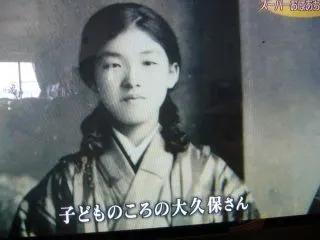

Aiko Ōkubo (Japanese: 大久保あい子) was a Japanese supercentenarian whose age has been validated by LongeviQuest.

BIOGRAPHY

Aiko Ōkubo was born in Mito City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, on 28 January 1913. Although she was named Kane (カネ) at birth, she went by the first name Aiko in her daily life. She was the second daughter among nine children, and her parents owned the first Western-themed restaurant in Mito City.

In 1934, she married a technical civil engineering officer from the Ministry of Home Affairs (now the Home Ministry of Japan). They had a total of four children. In 1938, due to her husband’s work circumstances, the couple and their three young children traveled across the sea to live in Manchuria in northeastern China, which was then a puppet state of the Japanese Empire. Initially, they lived in the capital of Xinjing (now Changchun), but moved repeatedly around Manchuria as the war progressed, at times forced to endure extreme temperatures of up to 40 degrees below zero during winter. Their lives were plunged even deeper into chaos with Japan’s defeat in the war when they were evicted from their home in Yingkou. After walking 20 km on foot to Dashiqiao—a journey said to be so perilous that some parents abandoned their children on the way—Ōkubo, her husband, and their three children were bundled into a freight train heading north without being told where they were heading. The couple believed if they continued northward much longer, they would never be able to return home to Japan. Feeling they had no choice, they decided to jump off the train with their children. After doing so, they found themselves in the city of Mukden (now Shenyang). At some point during their ordeal, Ōkubo cut off her hair with a kitchen knife, stating, “I didn’t know what might happen if people knew I was a woman.” After their long and tumultuous journey through China, which they barely escaped with their lives, Ōkubo and her family finally made their way onto a boat bound for Japan. They arrived in Maizuru City, Kyoto Prefecture, in June 1946 with nothing but the clothes on their backs. She cited her desperate wish to protect her children as the only reason she made it back alive. She returned to her hometown of Mito to find it completely burned down. Fortunately, her husband’s family was unharmed, and he would go on to inherit his family’s construction business.

In 1954, Ōkubo joined the Mito City Ethics Institute after spotting a poster titled “Lectures on Ethics: The Secret to Raising Children” in her neighborhood. She felt compelled to attend because, by this time, she was a mother to four children. Due to her firsthand experience of hardship and suffering during the war, she had a strong desire to raise them well and ensure they led happy lives. She believed in the importance of combining study with practice. After joining the Ethics Institute, she made a habit of waking up early every day to attend their daily “Early Morning Lecture,” which started at 5 am and lasted for an hour. Reflecting back on this time at the age of 102, she said she learned many things from the lectures: “Children are the best actors; they play the role of their parents.” Ōkubo came to believe that instead of making demands of her children, she should herself follow a disciplined lifestyle and lead by example.

Ōkubo’s children were all distinguished individuals in their own right: one became a university professor, another a doctor, and a third managed a private care facility for the elderly. She mentioned that her children growing up to become fine, well-rounded adults was her greatest source of happiness in life. In her 40s, Ōkubo took up writing tanka, a form of short Japanese poetry, on the advice of one of her Ethics Institute teachers.

In 2014, at the age of 101, Ōkubo participated in the Ibaraki War Exhibition, where she spoke about her experiences in Manchuria and the horrors of war. In June of the same year, she published her autobiography, which became so popular that additional copies had to be printed. At this time, Ōkubo lived in a 4-floor house with no elevator but moved around freely, climbing and descending the stairs several times each day.

Ōkubo believed that words possessed great power and made a point of never saying she was tired, no matter how busy she was: “Words can be a terrifying thing. As soon as you say ‘I’m tired,’ you really do get tired.” She took pride in her appearance, never leaving the house without first putting on her makeup and skirt. Ōkubo wasn’t picky when it came to food and was known to enjoy alcohol, with her drink of choice being highball, a popular type of whiskey cocktail in Japan.

RECOGNITION

Her age was verified by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW), as well as Yu Li, Yumi Yamamoto, and Jack Steer, and validated by LongeviQuest on 23 November 2023.

ATTRIBUTION

* “[ほのぼの@タウン]” Yomiuri Shimbun, 28 June 2011

* “「子どものため」必死に 101歳大久保さん、旧満州引き揚げの苦難回想/茨城県” Asahi Shimbun, 6 August 2014

* “子を守り満州引き揚げ 101歳・大久保さん、体験語る” Ibaraki Shimbun, 8 August 2014

* “102歳、あゆみ自叙伝に 水戸の大久保さん” Ibaraki Shimbun, 22 November 2014

* “『気と骨』”

Related Profiles

[crp limit=’4′ ]